Booming of the Community Land Trusts Model in France

Marc Uhry, Mayor of Villeurbanne Cabinet, may 2021

France has been quite late in answering the price neverending increase on housing markets, started more than two decades ago. And suddenly, French adaptation of Community Land Trust happens to pop-up everywhere. Some specificities, but perhaps also, some inspirationnal lessons to share.

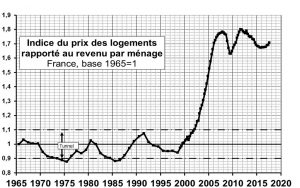

A late reaction to housing price bubble

From the late 1990’s the share of disposable income dedicated to housing went out of it’s long term tunnel. Several elements have lead to a lack of reaction. First, there were bubble peaks in the former decade and the fever ended in calming down, so this « crisis » was supposed to be short.

Second, the time was the starting point of a polarization between attractive metropolitan areas and shrinking small towns where the majority of French population still live. Politically, it was not essential to react to at a national stage and were blurred by shrinking markets.

Third, there is a collective confusion between level of price and level of profit. The general belief is that high prices are stimulating construction sector, good for employment of low-qualified workers, very important in a country weighted by an endemic unemployment over 10%. And there were very few hedge funds or pension funds deliberately attacking local markets, so real estate semt a quite healthy market.

Fourth and last, there is a strong social housing sector in France. Cities are bound by law to get a minimum of 25% social housing over the total housing stock, dedicated to 2/3 of the population. And on the other side, 54% of households are homeowners, not impacted and somehow interrested in price booming. There was allegelly not so many people impacted by such a bubble, onnly the newcomers on housing markets.

But, as prices remained very high, more than ever, for a long period of time, still going on, the whole housing sector was destabilized. The cheap private rental market vannished suddenly : in Lyon, second French city, half of private rental market was under social housing price in 1990 (mainly because of law quality). With perspective of higher rents, the stock has been refurbished quite fast and fifteen years late, only 3% of the private rental stock was still affordable. Average households then became dependant on social housing. Demand has exploded, while –at the same time- because of the gap between social housing and private market, the turn-over collapsed in social dwellings. Where you had three demanders for an offer in 2005, you find now ten demanders for an offer. To find a solution, households tend to move far, where land remain cheap, leading to a wide development of cities, soil impermeabilization, more individual transportation, terrible access to public services annd urban commodities.

This became also a political philosophy issue, for both sides. For the left, housing became the mean to make money circulate from the poors to the wealthiest. In marxist terms, the rent has became the vehicle of the « primitive accumulation of the capital. » For the right wing, celebrating brave independant workers, it became insane that you make more money with a single flat, waiting for prices to grow, than with an average income.

Even real estate complained because it needs more and more monney to buy land, and selling is more and more uncertain. Only banks were happy with longer mortgages, but with very low interrest rates, it is not even their best business.

In the middle of the 2000’s some people started to explore new ways to tackle speculation as such and not only through sideway means, such as land management, social housing. It became obvious existing tools were not sufficient and French people did something quite weird: learn from others.

Adapting the Community Land Trust model to the French context

Various pathways were leading to Community Land Trust. First, a cooperative growing movement was trying to find a status of shared anti-speculative ownership. The Greater Lyon was trying to build a tool for anti-speculative social access to homeownership, as a missing step between social housing and the market. The City of Lille was trying to avoid privatisation of public efforts, by a permanent duty binding households helped by tax relief, or having bought the social housing they were formally tenants.

The first serious thought came from Belgium, by professor of law Nicolas Bernard, who wrote a long article on how it’s possible to adapt the Community Land Trust mechanism to the Belgian legal framework. As France has a close civil law system with Belgium, CLT started to become a reference.

Very quickly, Brussels Region launched its own CLT, with public fund to buy land, for collective projects, in a cooperative spirit, targeting also poor people, migrants, etc, with equity brought by the region. High ambition but limited action, in a context whare social housing is missing (Brussels has about 5 times less social housing than a French same seizable city).

France has chosen an other option. What was missing was an answer for the low-middle class, something targetting anti-specuation and allowing people to become homeowners.

There was however a « constitutionnal barrier » to simply import the Community Laand Trust: in France, you can’t have a forever counterpart in a limited contract. So it’s impossible to permanently separate the ground and the building. France needed a specific new tool designed by law, to make it possible.

The French mechanism : l’Organisme de Foncier Solidaire et le Bail Réel Solidaire

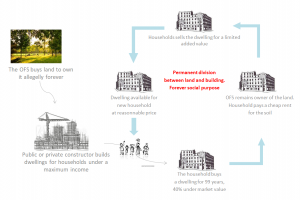

A law passed in 2014 has created the « Organisme de Foncier Solidaire » (« fair land trust »). This body is set up by a municipality or by housing associations, it’s dedicated to by land, through cheap long terms loans, 80 years, toward the Banque des Territoires, a public investment bank collecting French households savings, mainly to support social housing.

This land can then only be transferred through a « Bail Réel Solidaire » a new type of contract: a emphyteutic lease on 99 years, which restarts any time there is a new household in the dwelling. The buyer remains owner forever, until he or she sells the dwelling.

The buyer buy the dwelling and has to pay a rent for the soil: in Lyon, quite expensive city, only 1,15€/m2 each month. Because of tax relief on VAT linnked to social purpose, and thank to the very long term loan on the soil, dwellings are average 40% under the market price.

As a counterpart, they can’t be sold more than cumulated inflation.

Land has become a public good, average households can become homeowner and flets leave the speculative market, allegelly forever.

The dwelling is heritable, if newcomers fit requirements. To be elligible to the trust, two conditions: you need to be out of the 30% highest income and you need to make the dwelling your main home. There are 0% mortgage for households around median income. But the trust remains too expensive for low income who are still dependant on social housing, whoch is almost free for people with minimum income, supported by specific housing allowances.

Why it suddenly worked

First Organisme de Foncier Solidaire was created by Metropole of Rennes in 2018. Two years later, there were more than 60 bodies created are about to be, and the phenomenon is still accelerating, against all odds : complex mechanism, weird tenure. In 2022, 20 000 dwellings could by produced or bought through this mechanism, perhaps more. Even the creators – I am honourrd to be part of- were quite sceptical with the possibility for such a success.

So why ?

- It’s cheap. For OFS creators, cities or housing association, you don’t need a huge capital. Land is bought through a loan that is paid back by a cheap rent. As there is no amortization of the land in French accounting, the equity of OFS grows without end.

- It helps fulfilling local authorities obligations. Cities under market pressure have to save 25% of their stock for social housing. Missing social housing leads to expensive fines for them. Dwellings sold by OFS are considered part of social housing, and they are targetted to a working audience, more desirable than « justiciable right to housing » audience, for example, si cities are quite keen to develop this product.

- Useful to housing associations. Various recent national developments have weakened the balannce for social housing. To keep on producing they have to sell part of their stock (on the hypothesis that selling one amortized dwelling brings equity to build to new ones). Through the Bail Réel Solidaire, housing associations keep sold dwellings in the loop of social housing, they still own the land and they prevent indivduals to make big profits on public efforts to build and sell cheap.

- Useful to real estate developers, to meet working class again. Prices were too high for the average workers, which was becoming dangerous for developers as less and less households could afford to pay the price for their home. As OFS buys land, it’s cheaper for the buyer, but developers take the same amount of money; they can reach a broader target without doing efforts.

- Buyers bite it. Paris launched its 23 first flats in Bail Réel Solidaire, in april 2021. More than 26.000 households applied to buy them 5 000€/m2, which is still very expensive, but half the market price. This building was under media spot, but in other cities, even in suburbs or rather poor areas, more and more people are applying and not a single flat is sold with difficulty. The success also contributes to make Organismes de Foncier Solidaire a political sexy object, a must have, for any municipality ((including in shrinking areas, for other reasons)

- Community is only an option. The French adaptation of Community Land Trusts has been introduced into law, the same time as cooperatives of inhabitants. It’s possible for OFS to work for cooperatives (if cooperators fulffill social requirements, which is often an obstacle leading cooperatives toshift for another model). The main objective is to divide the cost and move out from speculation, so households don’t have to share some values or live closer to their neighbours. With rare exception for collective projects, the only thing in common is the land.

Then only thing in common is the land. Because we share it. And our home is our own property, the place of our intimacy. Who was crazy enough to start fencing the skin of Earth?

We are not only pushing back speculation, we are clarifying what belongs to each of us and what belongs to us all, meaning what we all belong to, starting with mother Earth.