Sans doute mon article le plus sérieux, « revue par les pairs » oblige… mais en Anglais. Pour la publication Loss of Homes and Eviction Across Europe. A Comparative Political and Legal Examination. (Elgar, 2018. s.d. Padraïc Kenna)

- Abstract/summary

France is an interesting country as it continues in quite a classic welfare state model, with extensive systemic tools including substantial borrowers rights, tenants’ rights, demanders rights under Roman law, allowances, a broad social housing stock and an obsession for universal equality, not always favourable to the best development for specific targeted policies.

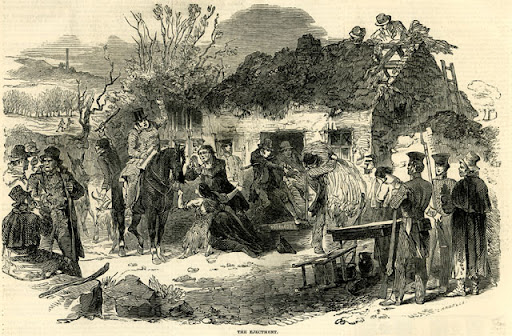

Evictions are one of these phenomenon, that systemic policies ought to prevent and that targeted measures are supposed to solve.As specific measures, such as fund dedicated to subsidizearrears, meeting proposal bu social workers, local commissions to prevent evictions failed to to challenge the rise of evictions, France has witnessed an increase in evictions over the past two decades.

This leads to a “French paradox”: here is a country where poor households are far less cost overburden than other European countries, but are more often in rent arrears, more often evicted through a long processin comparison with other EU countries?. France ranking on arrears is 4th in the EU, with 21,7 per cent of poor tenants in arrears, (EU average: 37,4 per cent), whereas France is only 25th on forced eviction, with 0,24 percent of the population evicted (EU average: 0,14 per cent). Evictions in Franc do not often lead to homelessness, but the homeless have often experience an eviction.

- Policy background

General housing policy related to evictions

For decades, forced evictions in France have affected mainly poor tenants and there have been very few repossessions??. In the late 1990s the prevention of evictions was a topic on the political agenda.. Between 1998 and 2008, a range of legal initiatives and administrative tools were established in order to “substitute a logic of social care to a logic of public order”, according to Louis Besson, the French Housing Minister at that time.

At the same time, over the past two decades?, France has been confronted with a re-emergence of squats and slums. In the late nineties Roma people and people from former Yougoslavia began to live in squats and slums, at a time when there was a peak of migration in France because of a civil war in Algeria. The phenomenon became more widespread / extensive (, despite the number of shelters opened. In 2014, the national administration (Dihal) calculated 400 -500 slums, where 17000 to 20000 people were living. In t same year, 150 forced evictions took place involving 13000 individuals. This issue is very evident on the public space of major cities, revealing terrible living situations, linked to migration and refugees.. The issues of migration and refugees are two sensitive topics, on the political agenda, but too emotional to be managedin an effective way.

Having regard to repossession, the main prevention policy stems from World War II, to make banks responsible for ‘irrelevant lending’. Banks are reluctant to lend money as they can be found responsible for the risk, which may go toward explaining the low level of repossession in France, compared to other EU countries.

In the French rental sector, the first factor to prevent evictions is the existence of a large social housing stock comprising 4 million dwellings, 18 per cent of the total houing?stock and individual allowances calculated at EUR17.7 billion in 2005, reaching20 per cent of the population. These two policies allow poor French households to pay less than other Europeans for housing.; When a household’s housing expenditure exceeds a certain threshold, established at 40 per cent of household revenue, the burden of this expenditure is considered excessive. Such overburden threatens the security and wellbeing of the household. This is what is meant by ‘housing cost overburden rate’…. In only two European countries, fewer than 15 per cent of poor households are overburdened by housing costs (Malta and Cyprus), followed by France and Finland (around 20 per cent). This might be explained by the large, affordable public housing stock and index-linked transfer incomes, as well as the composition of households in the latter two countries]. (rephrase)

The length of judicial proceedings fails to adequately explain this paradox. Judicial procedings last between eighteen month to two years, from the commencement of arrears to the effective eviction. This is one of the longest process in the EU. It is true that therefore, more households in arrears are in the scope of the Eurostat EU-SILC survey than in other countries where the process is shorter . But this explanation neglects the very high rate of court decisions with regard to evictions, compared with other coutries : 0.24 per cent of the whole population, almots twice more than EU average (0.14 per cent)

The figures relating to , cost overburden households, arrears and evictions, tend to show France has efficient systemic policies, to reduce the risk to be overburden, but these policies are not very effectual in blocking the process leading from arrears to evictions. This brings into question the specific policies related to evictions.

b) Structural/societal factors related to evictions e.g. unemployment, levels of debt, recessions etc

The strong welfare system in France makes it difficult to reveal the direct links between the socialcontext of households and eviction. Accordingly it is even more problematic to indicate the connection between structural factors leading to this very social context and then to eviction.

Moreover, the analysis is made arduous by the quality of data. For instance, there have been changes in the manner in which unemployment is recorded. Police practices and definition of what an “effective” eviction is, have also changed. In addition there has been a cessation of documenting mortgage arrears ,

France has only recently been affected by the economic crisis which took place 2007-2008. There was no housing market collapse, no jump in interest rates, and the slow rise of unemployment was damped by welfare system.Nonetheless , the social effects of the economic crisis were delayed, but not eradicated. .According to the National Employment Agency, the number of registered unemployed people in France increased from 3 million to 5 million, between 2007 and 2015. Whereas forced evictions were no longer on the political agenda, after a decade of new tools (dedicated fund to subsidize arrears, local commissions to prevent forced evictions, information given to social services before any court case,…) the delay between economic crisis, social difficulties and housing consequences came to an end. In 2015, forced evictions by police forces rose by 24 per cent in one year, to reach a total number of 14 363 forced evictions of tenants out of132 196 court cases stating a termination of lease.

Unemployment doesn’t necessary lead to housing difficulties and arrears. For households living in a “stable unemployment”, social rights are often optimized : they live in social housing, receive individual allowances, that make housing almost free. Local studies have shown how eviction are related to a change in households situation (loss of a job, health issue, break up in a couple,…)

Young households have specific difficulties. They are not in the scope of public protection in housing, because they have no right to minimum income. More, they are often in unstable situations, which are disadvantaged by the calculation system of individual allowances. The waiting time to access social housing is too long compared with their need for mobility. Young households often do not show guarantees as expected by the social housing, and consequently they have to move to the private rental sector which is more expensive, as they are in a more precarious situation. Young households are proportionally more affected by eviction than other groups.

- Specific policies related to evictions –e.g. moratoria, social support, State policies etc

There are a combination of measures and tools, concerning both the litigation procedure and the social aspects related to evictions? When arrears occur, a landlord must warn public authorities at least two months in advance of any litigation. Public bodies then write to the tenant to suggest a meeting with a social worker.

In each “Département “ (Shire), there is a «”Housing Solidarity Fund “, set up by lawand partially dedicated to lend or give money to households in arrears. social workers from public bodies are entitled to request this fund.

If a social worker does not request this fund? a landlord may request a a bailiff to give the tenant an order to pay. If the bailiff does not respond to the request, a landlord may go to the civil court. A judge is entitled to give a tenant up to three years to pay back his/her debt, with a monthly obligation. In theinterim, if a tenant is only one day late with repayment, the lease is terminated and the bailiff delivers an order to leave. If a tenant refuses to leave, a bailiff will call the police, who make a social inquiry and decide to force the tenant to leave or not.

In terms of rehousing, at any stage of the process, a collective instance, called Ccapex, has the authority to suggest more sustainable dwelling. Following the commencement of litigation, households affected are eligible to the justiciable right to housing (called Dalo) : The State has nine months to offer an alternative solution, a process which takeslonger than an eviction process. In theory the Dalo rehousing process is supposed to freeze the judicial proceedings, which is supposed to be suspended . This however is not always the case).

- Legal and constitutional background to protection against evictions

- Housing as a fundamental right

There is no mention of a right to housing in the French Constitution and no provision of the Constitution is mentioned in court cases. There is only one word in French for both property and ownership: “propriété”, which essentiallymeans ownership. Tenants have no property rights. The French Civil Code mentions ownership rights (art.544) and doesn’t mention right to housing. The French Administrative Supreme Court (le Conseil d’Etat), establishes a subtle hierarchy, considering ownership right as a constitutional right, and right to housing as a constitutional goal.: the State has to respect, fulfill and implement the ownership right and it only hase to pursue the right to housing.

Various legal instruments however, mention the right to housing as a fundamental right.

The provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure of Execution (CPCE), for instance, contains the obligation to have a court decision to proceed to eviction from a building or a “housing place”. () Articles L. 412-1 CPCE set out a framework on the execution of eviction decision made a judge. These articles apply to occupation of “ spaces used for / as main residential housing” (locaux affectés à l’habitation principale des personnes), which is subject to judicial interpretation.

Generally, these rules also apply to unauthorised occupation of housing (squatting) and to tenants without “lease or title”, but very rarely to occupants of a land.

Law n°89-462 (6 July 1989) is aimed at improving tenancy relations Article 1, provides that “housing is a fundamental right”. Law no 90-449 (31 may 1990) on“ implementation of right to housing” states that “guarantee the right to housing is a duty of solidarity for the whole nation.”

The law against exclusions aims to substitute a social approach instead of a public order approach, in eviction’ processes. In the private sector, the law establishes a pre-court phase during which social services are warned about impending evictions and contact tenant households. In the public sector, article 98 of the Social Cohesion Act (2005)of ?? establishes a soft law protocol between housing associations and tenants in cases of arrears, to plan an issue.

The law dealing with the opposable right to housing law (DALO) asserts that , the State is declared to be legally responsible for the right to housing, and shall provide a dwelling to any household who have been declared “prioritary”(that is to say in a priority situation targeted by the law) – for belonging to one of the six conditions defined as a priority target in the law, by the DALO commission of mediation (COMED) which includes involvement in an eviction procedure.

Law no 2009-323 (25 March 2009) of “mobilisation for the housing and fight against exclusion”, makes the generalisation of commissions of coordination of actions of prevention of eviction (CCAPEX) mandatory for all departments. This law imposes a social and financial inquiry, about household involved in an eviction procedure, to be transmitted to the judge at the moment of audience.

Law no 2014-366 (24 mars 2014) “For access to housing and to a renewed urbanism “(called ALUR), creates an obligation to inform the prevention of eviction Commission (CCAPEX) of any arrears of rent two months before the summons to attend hearing at the court, failing which the application shall be declared inadmissible. In addition, this law extends the period of the “winter break” (or “winter truce”) ensuring that no household can be evicted from the first day of November to the thirty-first day of of March. The “winter truce” does not suspend the procedure, but the execution of eviction. (CCH: art. L. 613-3). The law n° 2014-366 states that “eviction cannot be implemented between the first of November and the 31 of March of the next year” (art. 10 A / CPCE: L.412-6). ALUR also and extends the time – limits of a payment plan, to a maximum of three years. A judge may grant terms of payment if the re housing process requires it and he may also grant similar extensions after the notice to quit has been delivered, to leave the dwelling (art. 41).

From 1 the first of January 2015, the (ALUR?) law provides that landlords must report to the prevention of eviction commission (CCAPEX) on all cases involving of notices to pay which have been sent to their tenants, – in order to find alternative solutions before going to court (art. 27).

Law n° 2013.672 (26 July 2013) is aimed at strengthening the protection of mortgage borrowers and This law permits theto granting of extensions of the time-limits to over indebted owners facing an enforcement procedure and?, suspending the eviction procedure for a period of two years.

- Law relating to owner-occupation

In France, limited data is available about owner evictions, a matter not considered as a public problem and not monitored by public authorities, agencies, or defence of housing rights organisations. Only repossession procedure cases leading to effective eviction of the owner are recorded within a global category which does not distinguish between, owner, tenant or illegal occupant. (Reference!)

Having regard to legal mediation and preventative measures for borrowers facing eviction, the Civil Code provides for the extension of time limits. A judge can grant extensions of the time limits to a debtor in good faith up to a maximum of 24 months, allowing the debtor to reorganise the payment plan or with a deferment of debt. The procedure for a forced sale, that is a sale by auction, is then suspended by virtue of provisions in the Code of consumption.

“Fair price”. In case of an amicable sell, a the judge ensures that the sale is fair “fair price”– by considering the economic conditions of the market, and the estimated value of the good. A judge He establishes a minimum price under which the good cannot be sold.

The sale condition contract can also impose the new owner to keep the debtor in the house.

Suspension of enforcement (Code of consumption: L.331-3-1, L.331-5, L.333-2-1, R.331-11 and R.331-11-1)/ As soon as the debtor’s fill has been accepted by the over indebtedness commission (Commission de surendettement), the enforcement procedure is suspended. The over indebtedness commission may go to court in order to suspend the adjudication hearing, for serious and duly justified reasons. This supposes that the debtor has informed the commission as soon as he has been summoned to court for the orientation hearing.

The demand for a suspension of the enforcement sale must be made within the limits of 15 days before the planned date. As the judge does notdispose of any discretionary competence, the demand for postponement has to be justified. The duration of suspension cannot exceed two years and stops as soon as the decision of commission has become effective.

The borrower may ask for a juridical assistance (“aide juridictionnelle”) if he cannot afford a lawyer. Legal costs are covered by the State, at different rates according to the household’s incomes. (

- Law relating to private renting

The main law regulating private renting is the aforesaid Law no 89-462 of 6th July 1989, on renting relationship however there are still a few dwellings regulated by a former law n°48-1360, 1st September 1948.

As for evictions, the preventing eviction commissions, have been implemented in a very disparate way.

The social inquiry, planned to give a judge information to help him to make his decision and seek alternative solutions to eviction is not made systematically and are for the most very poor (no contact with household, no solution proposed). (do you mean the social inquiry is a weak measure it is unclear?

On preventive measures, contrary to what was asked by the circular letter of the 26 October 2012, in application of the law DALO (n°2007-290), affected households are not well informed. The three administrative Commissions managing allowances in case of arrears(CD-APL), monetary support to solve arrears (Fonds de Solidarité Logement – FSL), rehousing (Ccapex) are not sufficient and only 5% of households involved in a legal proceeding benefit from the Loi Dalo (wether these mechanisms can be useful by themselves to solve situations). This indicates

.

Having regard to judgments on evictions Since the law n °98-657, a judge has a real power of appreciation since the enactment of law no 98-657 (art 114). A judge can grant terms of payment to clear athe debt (law n°89-462: art. 24 al. 3 modified by the law n°2014-366 (art. 27 – V) and suspend the resiliation? of a lease

A judge may also cancel the lease, with or without granting extensions of time limits to pay or quit,

and in such cases, a judge orders the eviction. The decision shall be disclosed to the tenant, by deed of a bailiff, with the notice to quit under penalty of being declared void.

Finally, the decision ordering eviction must clearly indicate the possibility to refer to the DALO mediation commission .

When an owner wants to sell his/her property (“congé pour vente”) or when he/ she intends to regain the use of it, for himself or a family member (“congé reprise”), tenants of private rented housing may receive notices from their landlord obliging them to leave at the termination date of the lease, even if the tenant does not want to.

If the tenant is perceived to be unable to pay its debts, the judge will be less likely to grant him extensions, and will pronounce more quickly the order of eviction. 3 per cent – 4 per cent of court cases come are affecting these tenants without failing.

The Code of Civil Procedure on Execution (CPCE) contains a provision which provides for minimum income which the evicted debtor is entitled to retain, which is not confiscated/required to be paid in cases of arrears. Article L162-2 of CPCE states that in case of enforcement, the creditor cannot take a minimum income, called unattachable bank balance (ISB), which equals the minimum social income, the Revenu de Solidarité Active.

There are a number of Legal aid, mediation, conciliation,defence/appeals/alternative funding arrangements/ preventative measures for private renters facing eviction.

For instance, a tenant/ defender may ask the judge to grant him extension of terms of payment for the debts under the Civil Code. A

tenant/ defender may also ask a judge to grant him extensions of time limit before quitting a dwelling. In both cases, the duration of an extension cannot be less than three months or more than three years.

The execution of eviction can be suspended in the case of overindebtness file?. As soon as the debtor’s file? has been accepted by the over indebtedness commission (Commission de surendettement), the enforcement procedure is suspended and the commission has to apply the judge of execution.

The defender may appeal the decision under article 543 of Code of civil procedure, which provides that an “appeal is open, in all cases, against the first instance decisions” A defender must then address the court within 15 days from the decision in a “référé procedure”, one month for a judgment.

The tenant may ask for juridical assistance (“aide juridictionnelle”) if he cannot afford a lawyer and legal costs are covered by the State, at different rates according to the household’s incomes.

s(this paragraph need to be rephrases as it is unclear)

référé? does postpone , by virtue of law n° 2014-366 which states that “eviction cannot be implemented between the first of November and the 31 of March of the next year”. (art. 10 A / CPCE: L.412-6).

French law and policy also contains oObligations on landlords,/courts, and/bailiffs to inform housing or other agencies such as (e.g. social offices,) of the threat of eviction and are there any obligations of the latter (such agencies??) to respond. react A The landlord has to inform the housing benefits departmental commission (CDAPL) or the social services paying housing benefits (CAF, MSA) about any non-payment problem of a tenant, in order to attempt to clear the debt, before starting a legal procedure.

When a tenant receives housing benefit (APL), or when the housing benefit is paid directly to the landlord, the landlord has to inform the CDAPL within 3 months after the non-payment debt has started.

such as the and, must . (Law n° 2014-366 : art. 27 / CPCE : L.412-5).

Under The law n °98-657 (29 July 1998), a states that the bailiff has to inform the administration (Préfet) of a notice to quit??? two months before the hearing date, under penalty of being declared void (article 114). A copy of the notice to quit must shall be disposed to the Préfet by the bailiff.

The Préfet must remind the prevention of eviction commission (CCAPEX) and the household, of the possibility to apply to the DALO com mission since a notice to quit has been sent by the bailiff.

As of of

- Law relating to social renting

There is a very small proportion of the private rental sector dedicated to social purpose, through a agreement ? between the landlord and public bodies.. The agreement concerns support to renovate dwellings and tax relief, versus/set against? regulated rent. The lower the rent is for the longest period of time, the higher public support is. (These last two sentences are unclear)

However a large part of social renting is provided by social housing companies. Such companies can be public, private or cooperative, but all are regulated by law and they they must sign an agreement with the State.Activities such as allocation (of social housing are regulated by art.L441 and following, of the Code of Building and Habitat

The law on “social cohesion programming”, enables the continuity of housing benefits in social housing and suspends the eviction process, if an agreement protocol is signed between the landlord and the tenant. Legal proceedings, process and tenants protection are similar in social housing and in private rental sector.

the ?? (do you mean similar to?)

At At the stage of pre court stage, for example, wWhen a the tenant is receiving housing benefits, a public/ social landlord may be summonsed to attend a hearing only three months after the housing benefits commission (CDAPL, CAF or MSA) has been applied??? .(law n°2007-290 (DALO) : art. 28 / CCH : art. L. 353-15-1 and L. 442-6-1). The time limit can be reduced if the decision of the housing benefits ?commission is presented before the end of the three months. However, no control mechanism or sanction is provided in case the CDPAL is not applied, or if the period is not respected.

During the hearing, an agreement protocol can be signed between the landlord and the tenant(law n° 2005-32/ articles L 353-15-2 & L 442-6-5 du CCH). This protocol suspends the eviction process during the period of repayment of the debt and gives a title of tenancy and . tThe tenant can receive housing benefits during this time. If the tenant respects the payment plan, the landlord may propose a new lease for the same dwelling, in the time limits provided in the protocol.

- Law relating to unauthorised occupancy

The Art. L411-1 of Code for Civil Execution Procedures (CPCE)the state that any eviction cannot’t take place without a court decision, for all types of “inhabited constructions”.

This does not n’t include caravans illegally installed on a land, which has been placed under criminal law. (art. 322-4-1 of the Criminal Law Code (Code Pénal)). Under criminal law, there is a permanence of flagrante delicto, accordingly, so the police forces are entitled to stop the offence as soon as they see it.

For constructions, including slums, the Code of Civil procedure for executions (CPCE) contains provisions in relation to making arrangements in order to claim for a delay before eviction takes place.

Art. L412-6 of CPCE states there can be are no eviction in winter, except when the landlord can proves the occupyersoccupiers enterredentered by assault. Here the burden of proof is reversed in the sense that the (jurisprudence reverse the burden of proof : assault is alleged?? Claimed/declared, unless the defenders can prove prove otherwise, it was not the case, which makes the winter truce innot really effective).

Unauthorised occupancy refers to three legal procedures and three different courts.

The First Court (tribunal d’instance) for unauthorized occupancy of housings; The High Court (tribunal de grande instance) for unauthorized occupation (encampments, caravans, etc) of a land owned by a private person or belonging to the private domain of a public person ; The Administrative Court (tribunal administratif) for occupation (encampments, caravans, etc) of a land belonging to the public domain.

The Civil eviction procedure is set out inThe article 24 of the law n°89-462 (modified by law n° 2014-366). clears and sets out the civil eviction procedure. This procedure protects the tenants in cases of unpaid rent, ensuring all the steps and limits that shall be respected from summons to hearing to judgment, notice to pay and to notice to quit.

The provisions of the code of civil procedure of execution (CPCE) reminds of? the obligation to possess a court decision to proceed to eviction from a building or a “housing place”, and (art. L. 411-1 CPCE). Articles L. 412-1 et s. sets out a framework to execution of eviction decision made by the judge. These articles apply to the occupation of «” spaces used for / as main residential housing”» (“locaux affectés à l’habitation principale des personnes”). Generally, these provisions also apply to unauthoriszed occupancy of housing (squatting) and tenants without “lease or title”, but very rarely to occupants of a land.

When anthe occupied property is in the public domain and belongs to a public person?, the owner may/ must shall ask anthe administrative judge to order an eviction. But Tthis procedure however is far less structured/framed and protective than the procedure in front of a civil judge. The protection of occupants is within the discretionary power of this civil judge.

Legal procedures and processes to leading to evictions (stated at the beginning of this section)The bailiff role: pre-court convention, contradictory trial, non-contradictory trial.

The owner and the inhabitants ofan unauthorised occupancy may opt for a pre-court convention so as to avoid a legal procedure and this agreement must be reported and co-signed by the judge and parties (article 130, Code of civil proceedings).

If the occupants accept to be identified by the bailif, the bailiff makes a report (proces verbal) and summons them to attend a hearing. The owner can go to fast proceeding court (“« en référé” ») and ask the judge to order an eviction (art.808; 809 CPC).. The order is enforceable and shall be delivered to the occupants by a bailiff. At the same time, the bailiff delivers a order commandment to quit.

When the occupants refuse to be identified, or are not present, the eviction procedure is «” par requête” ». In this case, the owner can only request for eviction to the President of High Court. This is a non-contradictory procedure, without fair hearing. If the request is accepted, the judge gives an order, which is enforceable to the minute. In the situation where When the occupants refuse to quit, at he bailiff may request the public force ofto authorities (préfet).

Otherwise, the owner goes to court. The illegal occupant is summoned to attend a hearing in court by a bailiff, directly by a letter if the occupant is present, leaving a note if he is’s absent. If the owner is a landlord, he mayshall ask the bailiff to inform departmental authorities, soauthorities, so that they may pursue seek for re- housing possibilities.

Please remark: if the beilif is not in position to gt the names of inhabitants, the legal proceeding is then anonymous and inhabitants have no knowledge about it. They can’t ask for a delay before being evicted, for example.

When names are known and inhabitants are requested to the hearing, they may ask for an extension of time limits to quit the dwellingplace. From this moment, the process is the same for squatters, enterred by force in an empty dwelling, and for former tenants whose lease was canceled ater arrears.

Then, the judge notes the illegal occupancy and orders the eviction. The decision has to pronounce the eviction in his decision, failing which, the eviction cannot be effected. The decision of eviction shall be disclosed to the tenant, by deed of a bailiff, with the notice to quit, [under penalty of being declared void (law n° 91-650: art. 61 stating that every eviction has to be driven by a court decision)]. To be implemented, the decision of eviction shall be accompanied with a provisional enforcement order .so as to be implemented.

Request of police

The Préfet has two months to answer the request to quit?,- silence is deemed to indicate signal refusal (law 91-650: art. 17). The refusal must be justified, as the State is due to pay compensation to the landlord. The landlord may go to administrative court to demand compensation.

If the Préfet accepts the request, police forces take the responsibility to evict the occupants.

- Law relating to temporary dispossession – domestic violence, urban development family law issues etc.

Art. L641-1 of Building and Habitat Code, provides for states temporary dispossession (Réquisition) of homes, that are empty for at least 5 years , including a compensation to the landlords. Generally this law is not utilised owing to the low quality of vacant buildings and rather expensive compensation owed by the State to the landlord, make it not used in facts.

In cases involving domestic violence, Art. 220-4 of the Civil Code introduces a specific emergency court procedure to a the Family Judge (Juge aux Affaires Familiales), to forbid access to the home for authors of to violent spouses domestic violence. There But there is no possibility however to end the lease for one of the two members of a family in such cases, as this is considered a unilateral change in the contract opening the possibility for the landlord to end the lease for the remaining person.

The Expropriation Act (décret loi) from 30/10/1935 establishes permanent expropriation Expropriation is possible, after all other means have been explored and after an administrative phase determining the level of public interrest justifying such an expropriation.. The public body interrested then offers a compensation to the owner of the building.If the landlord does not accept expropriation or contests the level of the compensation proposed, the expropriation can be challenged in a civil court.

- Soft law/codes and their effectiveness

Public/social housing tenants may sign an agreement protocol with the landlord (law n° 2005-32/ articles L 353-15-2 & L 442-6-5 du CCH). This protocol suspendings the eviction during the period of repayment of a the debt and givinges a title of tenancy. The tenant can receive housing benefits in the meantime. If the tenant respects the payment plan, the landlord may propose a new lease for the same dwelling, in the time limits provided in the protocol.

There is no evaluation of this apparatus and, no data on the numbers signed.

- Extent of evictions over the period 2010-2015

| 2001 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | |

| Litigation to get an eviction order | 125 706 | 140 587 | 155 874 | 168 775 |

| -…for arrears | 107 639 | 128 782 | 145 384 | 159 812 |

| Court decision | nd | nd | 115 205 | 132 196 |

| Nb requests police forces | 36 400 | 40 417 | 42917 | 49 783 |

| Effective execution by police forces | 6 337 | 10182 | 11 670 | 14 363 |

Source : Ministry of Justice, Ministry of the Interior (this data includes squats and slums, when there is a court case, which is not always happening)

Data from Ministry of Justice don’t make sense in its coupling of housing repossession with ommercial activity. Collectively,Together, the number reaches 180.000, but it is impossible to say more than housing repossession are a tiny minority.

According to data reported by the Ministry of Interior, 2 992 orders for eviction because of illegal occupancy of land have happened in 2012, and 1 464 orders for eviction of illegally occupied builings.buildings were respectively of 2992 and 1464 in 2012. It must be notediced that data on illegal occupancyt of buildings (squatters) do not differentiate between illegal occupants (squatters) entering a place,, from ancient tenants staying in the place at the end of an enforcement procedure.

- Definition of eviction –

According to the report carried out by European commission there are three phases in terms of legal procedures processes and protections with regard to evictions; as per Evictions Report – pre court, court and post court.

Pre-court: there is no pre-court mechanism for repossession. As for tenants in arrears, there is an amicable mechanism (Commission de médiation) managed by both qualified persons, unions of tenants and landlords,… There is no obligation on the landlord to proceed this amicable instrument. Landlords can directly sue tenants, but they first, must send a baillif to deliver an order to pay (commandement de payer). Then and if arrears are not paid, at least two months before the court case, they have to notify the administrative local authority (le Préfet) who notify social services, who then write to tenants to offer support. At this stage only, landlords can go to court.

At court stage,: the first civil court (Tribunal d’Instance) is responsible for evictions decisions, including eviction from public properties. In illegal occupancies, there is a possibility for the landlord to request ask for an accelerated procedure (Référé).

At post-court stage, for all types of tenure, deferrals delays can be requested asked by defenders towards another procedure, to a specific judge (le Judge de l’Exécution).

When a decision is made, a baillif returns to the tenant to deliver an order to leave (commandement de payer) within two months. After these two months, the landlord is entitled to ask the administrative authority (le Préfet) for support from the police forces (demande de concours de la force publique). The administrative authority then asks the police to make a social enquiry, after which it decides whether to send the police and/or to activate a rehousing mechanism.

- Evictions from mortgaged property

As for mortgage, the competent court for the enforcement procedure for repossession is the court of first instance of the territory where the dwelling is located.

This order/ decree (ordonnance) states in its article 2191 that “any creditor (créancier) possessing an executor title stating a due claim may proceed to a seizure of property in conditions fixed by this law”. There is no minimum amount of non-payment of the loan.

When the borrower, who has not paid his loan normally, fails to doesn’t respond to a formal notice or reminder by letter, a notice to pay is sent by athe bailiff, mandated by the creditor – the creditor has to mandate a bailiff. It // The Formal notice ??? initiates the enforcement procedure (“seizure of property”). (CPCE: R.321-1, R.321-3 & R.321-5). The order to pay has legal value of seizure/enforcement (art 4, decree of the 27 July 2006)..

If the borrower does not pay within 8 days, a bailiff goes to the dwelling/ property to establish a statement of fact (“procès verbal”). Under penalty of being declared void, the committment to pay has to be published to the mortgage office (“bureau des hypothèques”) within the time frame the limits of two months. (CPCE: R.321-6 to R.321-10).

Within 2 months following the publication of the notice to pay, the debtor receives a summons to attend in court for an “orientation hearing”. (R.322-4 & R.322-5).

The conditions of the saleell contract must shall be filed to the court (R.322-10), before 5 days after the summons – under penalty of cancelling the summons (R.311-11). (Rephrase)

First Hearing (orientation hearing): during the First Hearing (orientation hearing) hearing, the judge of execution verifies (R.322-15 and sq) that all the conditions of civil procedure are fulfilled, and – in particular, that the creditor possesses an “executor title”, e.g. a title of a debt, in this case, a mortgage loan.

At this moment, the owner-debtor can request ask for an « amicable sell ».

“Amicable sale” The authorisation of an amicable sale means that the sale can be concluded in satisfying conditions, with regard to the location of the goods ands economic conditions of market. The judge establishes a minimum price, under which, the good cannot be sold. If the judge authorises the amicable sale, the enforcement procedure is suspended and

the judge sets a new date for a second hearing within the limits of four months.

At this second hearing, or if the sale is made and the judge orders the marking off mortgage,. the bailiff writes the sale which is approved ell by the and the judge. approves it. Alternatively, if the sale has not been made, for any reason, judge may grant an extension of three months for the debtor to pay his/her its debt, or order a “forced sale”. It should be noted that Please note: if the borrower, or a lawyer representing him, does not attend the hearing, the judge will automatically order a forced sale ell.

If the owner/debtor does not request an amicable sell, the judge sets out a date for the judicial sale, called a “hearing of adjudication”, within the limits of two and four months after the decision, for a forced sale.

- Risk factors identified leading to evictions from each housing tenure

Various local studies converge in identifying a number of risk factors leading to evictions in housing tenures, including households characteriszed by a wide spectrum of simultaneous difficulties, cluding : low income, health difficulties, stepfamilies and difficulties with the administration.,… The trigger catalyst seems often a recent decrease of income (including in numerous cases, move from wage to retirement pension), combined with the non take-up of various remedy paths.

As individual housing allowances are still high in France, and the social housing stock is quite high, a wide range of households with low income are almost housed for free. More, for househols with low wage on the private market, a set of remedies exist to pay back arrears. In such a welfare context, the income alone is not sufficient to trigger arrears and evictions.

- Links between evictions and homelessness –

There is no evidence that evictions are leading to homelessness. However, anthropological work with a small number of few former homeless people with multiple needs, demonstrates that such persons have been confronted with an eviction. Most of them have been confronted with to several evictions, that sometimes started in their early childhood.

- Summary of significant cases and reports related to evictions in the period 2010-2015.

There is Apparently, no major case-law with regards to evictions has occured in the last few years. (cf. http://cadis.semboules.free.fr/CadisExpulsionJurisprudence.htm)

- Best practice models for preventing, tackling and reacting to evictions

The GIP Charente Solidarités (Charente solidarities Public Interests Group),.

This structure coordinates all the actions for the of prevention of eviction in the department of Charente. The GIP manages the Fund of Solidarity for the housing (FSL), and allocates 15 per cent for the prevention of arrearst. A personalized support service is automatically proposed to any household involved in a procedure of eviction. The GIP is systematically writing a social report for the judge and to the Préfet, at all stages of the procedure. On his side, Tthe préfet is regularly consultsing the GIP social workers, before taking any decision concerning the intervention of the police in relation to evictions public forces. 80 per cent of households who met the GIP have attended the court hearing, and 72 per cent of households them obtained extensions of time limits from a judge. Conversely, 88 per cent of the households who did not meet the GIP and did not attend the court hearing had their lease cancelled without any extensions.

In 2013, 65 per cent (295) of the households / have found a “concrete housing solution”, – this figure is increasing every year (60.16% in 2012, 59.24% in 2011, 58.44% in 2010) : 41 per cent had a dwelling with a lease (99 in the private renting system and 23 in the public/social) ; 26 per cent had the debt cleared (77), 5 per cent in a transitional accommodation(15), 12 per cent living with family or friend (38).

As aforesaid mentioned before, such good practices seem to be more likely to be efficiently implemented in a restricted area, in terms of population, and when the housing market is not too high. Housing needs can be more easily satisfied, social workers can contact the households more easily, and, above all, stakeholders are able to work together.

Arrangements/provisions for removal and storage of the possessions of the evicted household

The procedure implies all the furniture and possessions of the evicted household to be removed, without any arrangements, at the tenant’s expense. The tenant has one month to remove its possessions from the write (“proces verbal”) of eviction. If not, the possessions are sold by auction. (law n° 91-650: art.65).

Having its social and financial costs, the aptness pertinence of the process of eviction can be questioned. On one hand, maintaining a household in his tenure appears to be far less expensive for public budgets than rehousing in a supported accommodation, as France provides a great number of various mechanisms and institutional systems to treat rather than to prevent or solve the eviction problem. On the other hand, the eviction process is frequently a traumatic experience for households, which removed from a stable and active participation into social life.

From this point of view, a global analysis of the costs of eviction could give arguments to reconsideration of the prevention mechanisms. Comparing the costs of eviction, including both rehousing and social consequences, and cost of prevention and stabilisation, would help to design more efficient policies.

Another example of best practice with regard to preventing, tackling and reacting to evictions is the more informal partnership in Lyon, where an NGO (Alpil), provides both is having social/legal advice together with barristers and employees from social services, to working both on housing aspects, legal aspects and social support, benefits, rights. This action takes place in the Court, at the same time as hearings on eviction cases, so that judges are able to send defenders to this specific service, when they feel they are not enough prepared and too vulnerable. Various local allocation committees are bringing together all housing associations present on the territory, social services, municipalities, NGO’s, both to prevent situations of eviction, and to rehouse situations that have been detected lately.

New improvement: the “descending pathway”, through which tenants facing difficulties can move from housing to supported homes managed by NGO’s, without litigation process. The global aim is to offer a pathway between supported accommodation and ordinary housing, tenants are able to use both ways.

As for private rental sector, real estates and landlords unions agreed on a protocol to facilitate alternative solutions to eviction. This is only goodwill protocol, but it gives a shared framework, an ethical backbone, to local stakeholders.

- Conclusion

France has a good systemic prevention system both for tenants and home-owners. However, despite a wide range of instruments, evictions are still high, despite most households leave before the police proceeds to the physical eviction. The absence of follow-up study of new situation of evicted households only lead to hypothesis. Through allocation systems and homeless services, there is still a possibility to bet a lot of them have not be rehoused immediately, but didn’t became homeless. Perhaps relatives play here an important role, not showable by existing data and research. People with in multiple needs, especially those suffering from psychiatric disorders, seem particularly vulnerable to the path from arrears to eviction, and from eviction to homelessness.

The lack of data about squats and slums does not rule out the increasing number of evictions in this field. The growing number of homeless and the migration crisis lead people to find more and more informal solutions. Despite a fast growing emergency and shelter system, demands from people sleeping outside keep on growing faster.

Perhaps, France’s numerous tools to prevent and solve homelessness are not adapted to the current situation, but possibly, this sophisticated system is slow and difficult to adapt to the constant evolution of social needs. There is here a room for international research, to understand more what type of policies, tools, organisation, are the most efficient to reduce causes of homelessness, including evictions.

- Bibliography

ADIL du Gard, (2012) « « Comment en arrive-t-on à l’expulsion ? 100 ménages expulsés de leur logement rencontrés par les ADIL « ,(2012) (“How does one arrive to be evicted? 100 households evicted from their dwelling met by the ADIL”), ADIL, 2012.

ADIL du Gard, (2011) « Les ménages menacés d’expulsion locative dans le Gard: profil et parcours logement », (The households threaten of renting eviction in the Gard : profile and residential trajectory), (2011) ADIL 2011.

ALPIL, “Etude action : les congés vente et reprise.(….) (2012) February 2012.

Brousse C, “Devenir sans domicile, le rester: rupture des liens sociaux ou difficulties d’acces au lodgement” (“to become homeless or staying it: breaking of social ties or difficulties to access to housing ?”) (2006 ) Economie et statistiques 391-392.

Brunet F et., Faure J,. (2004) “Les conséquences psychologiques et sociale de la procédure d’expulsion”, (“The psychological and social consequences of eviction procedure”), (2004) FORS- Recherche Sociale, Les cahiers du mal logement de la Fondation Abbé Pierre, October 2004.

Camille F. “Quelques déterminants des décisions de justice en matière d’expulsion locative “,(Some determinants of the justice decisions about renting evictions) December 2013.

Camuzat S. (2012) “Prévention des impayés et des expulsions: pour une intervention précoce et la mise en place d’un dispositif villeurbannais dédié à cette question” (Prevention of non payment and evictions : for an early intervention and the implementation of a dedicated system in Villeurbanne) (2012) AVDL, October 2012.

Cléach M.P. rapport d’information au nom de la commission des Affaires économiques et du Plan (1) sur le logement locatif privé, (2003) (Information report in the name of the economics affair and the Plan on the private renting housing), 15 October 2003.

Grunspan J. P. « Définition d’un système d’information des expulsions locatives, de leur mécanisme et de leur prévention », Definition of a information system of renting eviction, mechanisms and prevention), Conseil Général des Ponts et Chaussées, July 2004.

Herbert, B. (2011) « Prévention des expulsions ; locataires et bailleurs face à l’impayé », (prevention of evictions ; tenants and landlords face to non payment), ANIL, October 2011.

Maury N., Bily E. “La construction d’une instance nouvelle de prévention des expulsions: la mise en place des CCAPEX”, (The construction of a new instance of prevention of evictions: the implementation of CCAPEX), (2012) ANIL, January 2012.

Nivière D. “ »Les ménages ayant des difficultés à payer leur loyer” », (Households with difficulties to pay their rent), Direction de la Recherche, des Etudes, de l’Evaluation et des statistiques (DREES), Ministère de l’Emploi, de la Cohésion Sociale et du Logement, Etudes et Résultats n°534, November 2006.

Vorms, B. (2010) Intervenir de façon précoce pour prévenir les expulsions, (To act early to prevent evictions), (2010) Rapport du Directeur Général de l’ANIL pour le Secrétaire d’Etat chargé du Logement, 2010.

Cléach M.P. Rapport d’information au nom de la commission des Affaires économiques et du Plan (1) sur le logement locatif privé, (2003) (Information report in the name of the economics affair and the Plan on the private renting housing), 15 October 2003.